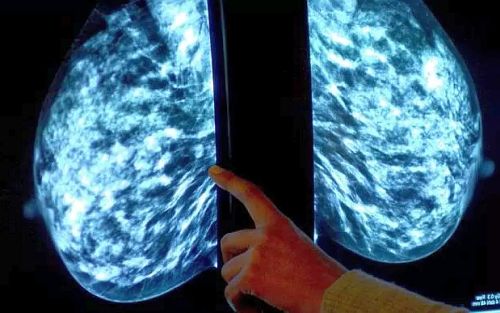

Thousands of women with the most deadly form of breast cancer could be given hope by a breakthrough treatment which could make chemotherapy effective.

Charities hailed the advances as “hugely exciting” and said they could help cancer patients with few other options.

The drug – already in trials as a leukaemia treatment – attacks cancer cells that have become resistant to chemotherapy.

This allows standard drugs to start working again, destroying the tumour.

Scientists believe it could transform care for the 7,500 women a year diagnosed with “triple negative” breast tumours.

Such cancers are more common in younger women, and are often aggressive, failing to respond to many of the main forms of treatment.

About | Breast cancer

- Signs and symptoms of breast cancer:

- A change in size or shape of the breast

- A lump or thickening that feels different from the rest of the breast tissue

- Redness or a rash on the skin and/or around the nipple

- A change in skin texture such as puckering or dimpling

- Discharge (liquid) that comes from the nipple without squeezing

- Nipple becoming inverted or changing its position or shape

- A swelling in the armpit or around the collarbone

- Constant pain in the breast or armpit

- What to do if you find a change:

- Most changes are likely to be normal or due to a benign (not cancer) breast condition

- If you notice a change, visit a GP as soon as possible

- A GP may feel there is no need for further investigation or may refer you to a breast clinic

- If you do not feel comfortable with a male GP, ask if there is a female GP available

In a new study, scientists have identified the role of a molecule called PIM1 in driving and controlling triple-negative breast cancers.

The research found that in the majority of such cancers, the molecule has been hijacked and over-produced, helping cancer cells to survive, in the face of chemotherapy.

Researchers said targeting PIM1 and inhibiting production – could be key to successfully treating women who might otherwise have no hope.

Scientists said the study, by King’s College London and The Institute of Cancer Research, London, could see trials starting on women with breast cancer within two years.

Baroness Delyth Morgan, chief executive at Breast Cancer Now, said: “This is a hugely exciting advance for an important group of patients in desperate need of more treatment options.

“Triple negative breast cancer is often aggressive and more common in younger women, and chemotherapy drugs remain the only option for these women. While these work very well for some, if patients’ cancers become resistant there are few other options.”

A new targeted treatment for such patients would be a “major breakthrough” she said.

Current trials of the drugs on patients with leukaemia suggest they are well-tolerated, giving grounds for optimism, she said.

“Triple-negative” cancers lack the three receptors which are normally used to classify breast cancers: those for oestrogen, progesterone and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). This means they cannot be treated with targeted drugs commonly used to interfere with these receptors, such as tamoxifen and aromatase and Herceptin.

As a result, patients have few treatment options – typically chemotherapy in addition to surgery and radiotherapy.

Professor Andrew Tutt, from the Institute of Cancer Research, said: “Many triple negative breast cancers are very resistant to chemotherapy and are ‘driven’ by genes that are very difficult to target with drugs.”

The findings, published in Nature Medicine, suggest that the drugs “could strip triple-negative breast cancers of their defences so that they can be pushed over the cliff by other breast cancer treatments,” he said.