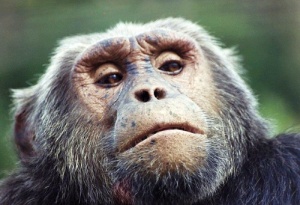

A Danish drug tested on San Antonio chimpanzees is showing promise as a new gene-based therapy that fights hepatitis C and potentially other diseases.

A Danish drug tested on San Antonio chimpanzees is showing promise as a new gene-based therapy that fights hepatitis C and potentially other diseases.

The drug, developed by biopharmaceutical firm Santaris Pharma doesn’t directly fight the virus, which is quick to develop drug resistance.

Instead, it targets and locks down a gene in the liver that the virus needs in order to replicate, said Robert Lanford of the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research.

“The high barrier to resistance makes it one of the most attractive drugs we’ve seen,” said Lanford, lead author on the study that appeared in the Dec. 3 issue of Science Express.

An estimated 3.2 million people in the United States have hepatitis C, or HCV, and many don’t know it, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It can range from a mild illness lasting a few weeks to a lifelong disease that may not become apparent for years, and can lead to cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Santaris’ “locked nucleic acid” or LNA technology uses a DNA-based drug called SPC3649. It was given to four chimpanzees at the Southwest Foundation that were infected with chronic hepatitis C virus.

Huge drop in viral levels

The two chimpanzees that received higher doses of SPC3649 had a 350-fold drop in the viral levels in the blood and liver, Lanford said. The animals, which are the only other creatures besides humans that can be infected with HCV, were given one dose a week for 12 weeks. Not only did they not develop resistance to the drug, which usually happens with days, Lanford said, but the virus stayed suppressed for several months after researchers stopped the therapy.

“Not only did we knock down the virus, but we saw an improvement in the liver itself because we could keep the virus down so long,” he said.

It’s also a promising platform for gene therapy, a technology that has been frustrating scientists for some time, Lanford said.

Normally, DNA-based drugs are not stable in the body, he said.

They get degraded in the body and they just don’t bind as well” to the gene involved.

Releasing the drug is still several years off. It has moved into Phase I trials in healthy humans to see if there are adverse effects, Lanford said, and then must go through two more phases of extensive testing in humans.

Santaris contracted with Southwest Foundation for the preclinical trial because “we’re one of the few places that has chimpanzees,” Lanford said