Iron overload is a major concern in patients with thalassemia. For years, scientists have believed that this problem exists only in patients with a more severe form of the disease, thalassemia major. However, they now realise that even those with the milder form of the disease, thalassemia intermedia, have high blood levels of iron.

Researchers at the Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, along with a group of international scientists have discovered a genetic relationship that causes dangerous iron overload in persons with beta-thalassemia. According to their discovery, an imbalance in the levels of two proteins, one that controls iron intake (hepcidin) and the other that controls iron transport in the body (ferroportin), causes too much iron to enter the body through the intestine, heightening iron to very unhealthy levels.

Researchers at the Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, along with a group of international scientists have discovered a genetic relationship that causes dangerous iron overload in persons with beta-thalassemia. According to their discovery, an imbalance in the levels of two proteins, one that controls iron intake (hepcidin) and the other that controls iron transport in the body (ferroportin), causes too much iron to enter the body through the intestine, heightening iron to very unhealthy levels.

Says Dr. Stefano Rivella, the study’s senior author, “For years, scientists believed that blood transfusions, a dire requirement in thalassemia major, was the cause for iron over load in patients. They soon realised that even in patients with thalassemia intermedia, where blood transfusions were irregular or not done at all, iron overload was present. The iron loading in thalassemia depends on the volume of blood transfused and the amount accumulated from gut absorption. Gut absorption is particularly important in thalassemia intermedia. In thalassemia major, increased absorption is inversely proportional to the mean post-transfusional haemoglobin.”

Anything in excess isn’t necessarily good, as with excess iron in the body. Excessive iron is the cause of many serious complications, severely affecting the liver, heart and endocrines, leading to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and cancer; heart failure; growth impairment; diabetes; and osteoporosis. Chelation therapy that drains excess iron from tissues is required in such individuals.

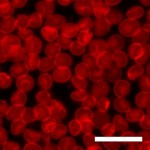

To unravel the mystery about the disease which encourages such iron absorption, Weill Cornell researchers, along with colleagues at Oporto University in Portugal, Tel-Aviv University and the Hebrew University in Israel, and Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston, investigated iron overload, using sophisticated, genetically engineered mouse models of beta-thalassemia.

They discovered that an increase in expression of gene Hamp1 (that signals hepcidin to slow iron intake from the intestine) is accompanied by an equal increase in expression of Fpn1 (that signals ferroportin to transport iron from the gut into tissues), thus eventually increasing iron levels in the body.

This whole new paradigm for chronic iron overload in patients with the intermedia form of the beta-thalassemia, has paved a way for a better treatment approach. “It shows that if we keep doing what we are doing — modulating hepcidin levels in blood — we can still manipulate this relationship to get iron absorption under control in both the major and intermedia forms of the illness,” Dr. Rivella says. “That’s great news.”

Beta-thalassemia is one of the most common inherited forms of chronic anaemia, with incidence highest in Southeast Asia, the Middle East and Africa. The disease is caused by mutations in the beta-globin gene, which governs the production of haemoglobin.