American researchers develop a new human stem cell that may be easier to manipulate

American researchers have developed a new type of human stem cell that may be easier to manipulate.

American researchers have developed a new type of human stem cell that may be easier to manipulate.

Researchers from the Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Regenerative Medicine (MGH-CRM) and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute describe the development in the June 4 Cell Stem Cell.

These new cells could be used to create better cellular models of disease processes and eventually may permit repair of disease-associated gene mutations.

Niels Geijsen, of the MGH-CRM, who led the study, said: “It has been fairly easy to manipulate stem cells from mice, but this has not been the case for traditional human stem cells.

“We had previously found that the growth factors in which mouse stem cells are derived define what those cells can do, and now we’ve applied those findings to human stem cells.”

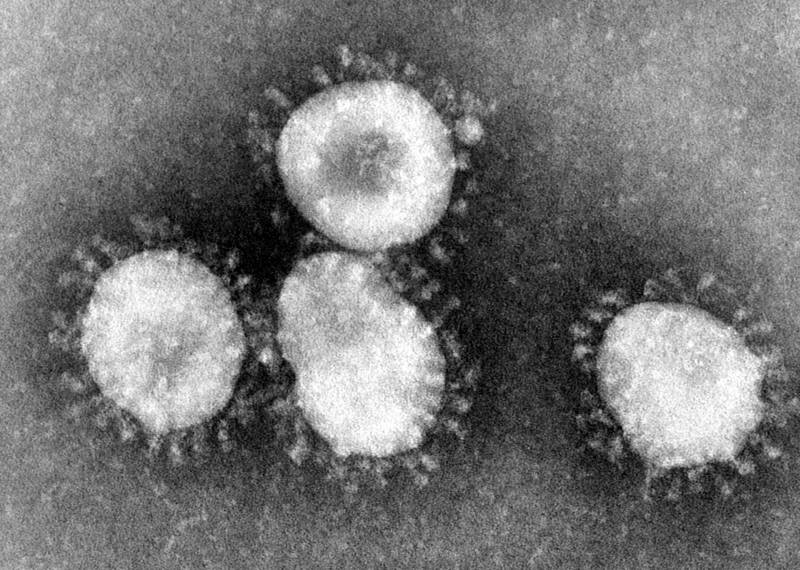

The first mammalian embryonic stem cells (ESCs) were derived from mice and have proven very useful for studying gene function and the impact of changes to individual genes.

But techniques used in these studies to introduce a different version of a single gene or inactivate a particular gene were ineffective in human ESCs.

In addition, human ESCs proliferate much more slowly than do cells derived from mice and grow in flat, two-dimensional colonies, while mouse ESCs form tight, three-dimensional colonies.

It is been extremely difficult to propagate human ESCs from a single cell, which prevents the creation of genetically manipulated human embryonic stem cell lines.

In previous work, Geijsen and his colleagues demonstrated that the growth factor conditions under which stem cells are maintained in culture play an important role in defining the cells’ functional properties.

Since the growth factors appeared to make such a difference, the researchers tried to make a more useful human pluripotent cell using a new approach.

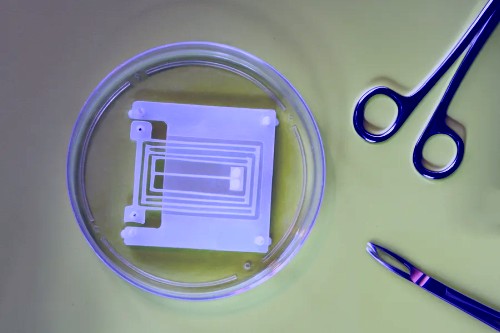

They derived human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) – which are created by reprogramming adult cells and have many of the characteristics of human ECSs, including resistance to manipulation – in cultures containing the growth factor LIF, which is used in the creation of mouse ESCs.

The resulting cells visibly resembled mouse ESCs and proved amenable to a standard gene manipulation technique that exchanges matching sequences of DNA, allowing the targeted deactivation or correction of a specific gene.

The ability to manipulate these new cells depended on both the continued presence of LIF and expression of the five genes that are used in reprogramming adult cells into iPSCs.

If any of those factors was removed, these hLR5- (for human LIF and five reprogramming factors) iPSCs reverted to standard iPSCs.

“Genetic changes introduced into hLR5-iPSCs would be retained when they are coverted back to iPSCs, which we then can use to generate cell lines for future research, drug development and someday stem-cell based gene-correction therapies,” said Geijsen

Courtesy ANI

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.