Stanford Developed Laser System Shows Promise For Cataract Surgery

Imagine trying to cut by hand a perfect circle roughly one-third the size of a penny. Then consider that instead of a sheet of paper, you’re working with a scalpel and a thin, elastic, transparent layer of tissue, which both offers resistance and tears easily. And, by the way, you’re doing it inside someone’s eye, and a slip could result in a serious impairment to vision.

This standard step in cataract surgery – the removal of a disc from the capsule surrounding the eye’s lens, a procedure known as capsulorhexis – is one of the few aspects of the operation that has yet to be enhanced by technology, but new developments in guided lasers could soon eliminate the need for such manual dexterity.

A paper from Stanford University School of Medicine, published in Science Translational Medicine, presents clinical findings about how one new system for femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery is not only safe but also cuts circles in lens capsules that are 12 times more precise than those achieved by the traditional method, as well as leaving edges that are twice as strong in the remaining capsule, which serves as a pocket in which the surgeon places the plastic replacement lens.

“The results were much better in a number of ways – increasing safety, improving precision and reproducibility, and standardizing the procedure,” said Daniel Palanker, PhD, associate professor of ophthalmology, who is the lead author of the paper. “Many medical residents are fearful of doing capsulorhexis, and it can be challenging to learn.

This new approach could make this procedure less dependent on surgical skill and allow for greater consistency.” The senior author is William Culbertson, MD, professor of ophthalmology at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute at the University of Miami.

While the technology to perform this new approach – called a capsulotomy instead of capsulorhexis – is being developed by a number of private companies, this paper focuses on a specific system being produced by OpticaMedica Corp. of Santa Clara, Calif., which funded the study. Palanker, Culbertson and five other co-authors have equity stakes in the company; the remaining seven co-authors are company employees.

Cataract surgery is the most commonly performed surgery in the nation, with more than 1.5 million of these procedures done annually. The operation is necessary when a cloud forms in the eye’s lens, causing blurred and double vision and sensitivity to light and glare, among other symptoms.

The current procedure involves making an incision in the eye and then performing capsulorhexis: in that step, the paper explains, “The size, shape and position of the anterior capsular opening … is controlled by a freehand pulling and tearing the capsular tissue.” After that, the lens is broken up with an ultrasound probe and suctioned out.

The surgery culminates with the placement – as snugly as possible – of an artificial intraocular lens in the empty pocket created in the capsule. Before closing the eye, the surgeon may make additional incisions in the cornea to prevent or lessen astigmatism.

With the new system, a laser can pass through the outer tissue – without the eye being opened – to cut the hole in the capsule and to slice up the cataract and lens, all of which occurs just before the patient enters the operating suite.

The laser also creates a multi-planar incision through the cornea that stops just below the outermost surface, which means that the surgeon needs to cut less once the operation begins, as well as decreasing the risk of infection.

Because of the laser work, once the operation is under way, the removal of the cut section of the capsule and the sliced-up lens can be done relatively easily, with much less need for the ultrasound energy.

Femtosecond lasers, which deliver pulses of energy per quadrillionths of a second, were already being widely and successfully used to reshape the cornea of the eye to correct nearsightedness, farsightedness and astigmatisms. For use in cataract surgery, however, the laser would need to cut tissue deep inside the eye.

While the laser would need to reach a level of intensity strong enough to ionize tissue at a selected focal point, it would also have to have pulse energy and average power low enough to avoid collateral damage to the surrounding tissue, retina and other parts of the eye.

Palanker and his team found the proper balance through a series of experiments on enucleated porcine and human eyes. They then did further experiments to confirm that a laser at those settings would not cause retinal damage.

Still, a major hurdle remained. The laser needed to be guided as it made its incisions to ensure that it did not go astray, cutting nearby tissue, and that it would meet exacting specifications for the size of the disc-shaped hole in the lens capsule that it would be creating.

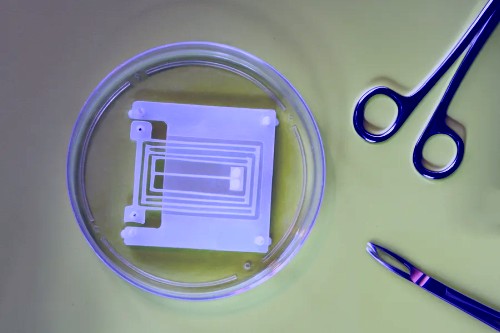

The solution? Use optical coherence tomography – a noncontact, noninvasive in vivo imaging technique – to get a three-dimensional map of the eye. Using that image, he and his colleagues developed software that pinpoints the ideal pattern for the laser to follow.

It is then superimposed on a three-dimensional picture of the patient’s eye, so that the surgeon can confirm it’s on track before starting the procedure, in addition to monitoring it as the cutting proceeds.

“Until this, we had no way to quantify the precision, no way to measure the size and shape of the capsular opening,” Palanker said.

A clinical trial in 50 patients revealed no significant adverse events, supporting the study’s goal of showing that the procedure is safe. What’s more, the laser-based system came much closer to adhering to the intended size of the capsular disc (typically coming within 25 micrometers with the laser vs. 305 micrometers in the manual procedure).

And using a measurement that ranks a perfect circle as a 1.0, the researchers found that the laser-based technique scored about .95 as compared with about .77 for the manual approach to cutting the disc from the capsule.

What this means is that when the plastic intraocular lens is placed in the capsular bag, it’s going to be better centered and have a tighter fit, reducing the chances of a lens shift and improving the alignment of the lens with the pupil.

This is increasingly important as more patients choose to have multifocal and accommodating lenses, which need to be aligned more precisely with the pupil to function well.

The laser-assisted surgery offered other benefits aside from the capsulotomy. The paper notes that because the laser has already spliced the lens, there’s less need to use the ultrasound probe. Its excessive use in hard cataracts can sometimes create too much heat and damage the corneal endothelium and other surrounding tissue.

The laser also can create a multi-planar zigzag pattern for the incision in the cornea, allowing the incision to self-seal and decreasing the likelihood of infection and other complications.

While not an endpoint of the study, the researchers found that the new procedure did improve visual acuity more than the traditional approach; however, the difference was not statistically significant due to the small number of patients enrolled.

Palanker said a properly designed clinical study is needed to quantify improvements in vision with various types of intraocular lenses; such research may take place in the United States if the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approves the new machine. Data from Palanker’s study is going to be submitted to the FDA for consideration.

“This will undoubtedly affect millions of people, as cataracts are so common,” said Palanker, though he expects that it will take time for the new procedure to be adopted.

At present, the new procedure takes longer than the current standard, and it would cost more, with Medicare unlikely to cover it in the immediate future.

“But there will be people who elect to have it done the new way if they can afford it. There are competitors coming out with related systems. This is what’s exciting. This technology is going to be picked up in the clinic.”

Source: Jonathan Rabinovitz

Stanford University Medical Center

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.