University of Minnesota Organ Transplant Spin-Off moves Closer to Reality

12th August 2009 Minnesota USA – The University of Minnesota-bred start-up, based on the regenerative tissue work of Dr. Doris Taylor, will be called Miromatrix Inc. (It seems like any biomedical company worth its salt must have an “x” in its name).

12th August 2009 Minnesota USA – The University of Minnesota-bred start-up, based on the regenerative tissue work of Dr. Doris Taylor, will be called Miromatrix Inc. (It seems like any biomedical company worth its salt must have an “x” in its name).

The company, which is developing a way to grow transplant organs in labs, has no offices or Web site yet, but it’s a safe bet that Miromatrix will remain in Minnesota since CEO Robert Cohen, a former top executive at St. Jude Medical and Travanti Pharma, lives in Edina.

“After the success with my team in building Travanti Pharma over the past five years and selling it to Teikoku Pharma in May, those of you who know me well understand that I would not have accepted another early stage CEO position for any ‘normal’ technology and opportunity,” Cohen wrote in an e-mail obtained by MedCity News. “The Taylor technology truly excites me. Not only is it a very clever development for which several patent applications already have been filed, but it also applies to enormous potential markets.”

Cohen declined to comment further.

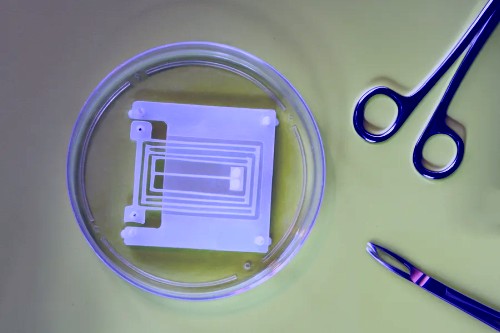

Last year, Taylor and her team successfully grew a rat’s heart in a jar by stripping the cells off a dead rat’s heart and then injecting cells from a live rat into the organ. In addition, Taylor designed a bioreactor that could successfully nurture the nascent heart with blood and oxygen in a sterile environment. An artificial womb, if you will.

Theoretically, the technology can grow human hearts from a patient’s own cells, which allows the body to more readily accept the transplant.

“Organ failure is a major cause of death today,” Cohen wrote. “In the United States alone, more than one million people die of organ failure each year.

Despite the fact that organ transplantation surgical techniques have been in common use for many years, the shortage of organ donors is a serious gating factor on the usefulness of these techniques.”

“As a result, the United States spends approximately $140 billion on ‘organ replacement therapies’ annually, impacting the lives of more than 20 million people,” he continued. ” This includes many widely accepted therapies such as dialysis, CRM devices and stents.

These therapies are necessary because the injured organ cannot be replaced or repaired. They are, however, suboptimal. We intend to change all of that.”

To say that Miromatrix means everything to the U, and indeed Minnesota, would be an understatement. U officials say Taylor’s work is blockbuster stuff with the potential to put Minnesota on the biotech map the same way Earl Bakken’s pacemaker did with implantable medical devices more than 40 years ago.

However, growing organs is no simple task and it could take decades to vet the technology. To pay the bills, Miromatrix plans to sub-license its technology to other medical applications. For example, the company envisions drug companies testing their therapies on blocks of tissue grown by Miromatrix, a process that could greatly speed clinical development and reduce potential side effects.

And of course, the company needs to raise money. Fearful that Miromatrix could fly the coup the same way other promising U spin-offs, like VitalMedix Inc., fled Minnesota, public officials have been seriously looking at ways for the state to directly invest in the start-up, which has also drawn interest from venture capital firms on both coasts.

By all accounts though, Miromatrix will raise the necessary $1 million or so from local investors by the end of the year.